Teotihuacan Research Laboratory

About Teotihuacan

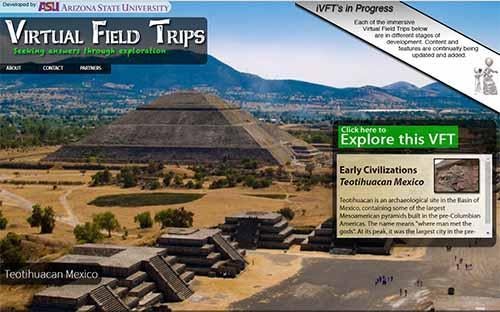

Teotihuacan was an immense city that flourished in the highlands of central Mexico, near modern Mexico City, from about 100 BC to AD 650, long before the Aztecs of the 1400s. It covered about 8 square miles and housed around 80,000 people. Teotihuacan was one of the largest ancient cities anywhere in the world. Its influences were strongly felt throughout central and southern Mexico, and impacted even the distant Maya of Yucatán and Guatemala.

Teotihuacan is a UNESCO World Heritage site; the millions of tourists who visit it every year are awed by its vast ceremonial center, its art and its immense pyramids--among the largest anywhere in the ancient New World and comparable to the largest in ancient Egypt. However, most of the city is still unexcavated and not seen by tourists.

Multiple archaeological projects are ongoing, carried out by Mexican and other institutions. Arizona State University faculty and students play a leading role in these projects, and ASU maintains a large research facility adjacent to the site.

Unlike many ancient cities, much of the archaeological site is not deeply buried under modern settlement. Because of this, archaeologists can excavate and reconstruct large parts of the city and create an unprecedented story of ancient urban life.

Teotihuacan has much to teach us about the origins and declines of cities, alternative forms of government, the nature of ancient urban life and the ways that religion, governance, markets and economies can change through time. These and many other questions about the ancient city can be answered only if archaeologists continue their fieldwork at the site.

As archaeological methods continue to improve, excavations are becoming more informative and Teotihuacan is beginning to give up its secrets to science. These advances are the fruit of international and inter-institutional collaborations, in which the ASU-managed archaeological facility at Teotihuacan plays a vital role.

For more information, see the following blog posts about Teotihuacan:

About the ASU Teotihuacan Laboratory

In partnership with Mexico’s Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, archaeologists from Arizona State University have been conducting fieldwork at Teotihuacan for nearly 50 years. ASU is privileged to have the opportunity to manage a facility at Teotihuacan that provides a space for teams of students and researchers to study one of the largest cities in the ancient world. Unlike many archaeological sites, Teotihuacan is not buried deep under modern settlements; this gives us a unique opportunity to perform excavations and explore the lives of its residents. We recognize the importance of the past for the outcome of the future and use our discoveries at Teotihuacan to study topics relevant to modern societies, such as alternative governmental systems; how cities rise and fall; and the ways that religious and economic practices change over time.

The artifacts uncovered by ASU and its Mexican partners, the legacy of this ancient city, are housed at ASU’s Teotihuacan Research Laboratory in San Juan Teotihuacan, Edo. de México.

The ASU-managed facility at Teotihuacan is part of the School of Human Evolution and Social Change in The College of Liberal Arts and Sciences.

It was initiated by professor René Millon, of the University of Rochester, who directed the detailed mapping of the entire city in the 1960s. He combined air photos and mapping with surface reconnaissance of over 5,000 individual tracts, making notes on visible features and collecting nearly a million pottery fragments and other ancient objects from the surfaces of these tracts. His Mapping Project remains unique for its combination of scale and detail. It is an indispensable basis for planning further work at the city.

ASU research professor George Cowgill took over as director of the present laboratory location in 1986 with assistance from the National Science Foundation, following Millon’s retirement. Today it houses the materials collected by a number of projects besides Millon’s Mapping Project, and provides housing and work space for up to 10 researchers, including students, with a total floor space of about 1,160 square meters.

Professor Michael E. Smith, a renowned Mesoamerican expert and archaeologist, took over directing the lab in 2015.

Overview of the Ancient City

By research professor Saburo Sugiyama

The ceremonial center of Teotihuacan was characterized by its exceptionally precise urban planning, a consistent orientation and its outstanding monumentality, represented by three pyramids: the Pyramid of the Feathered Serpent, the Pyramid of the Sun and the Pyramid of the Moon.

The monuments and housing compounds that spread over more than 20 square kilometers apparently operated as a ritual and pilgrimage center originally, and then became a truly metropolitan city where intra- and interstate socio-economic activities took place well beyond the Mexican Central highland areas.

However, Teotihuacan was mostly destroyed sometime during the 6th century, with still unspecified reasons. The city was thereafter target for looting or mortuary activities, gradually becoming a legendary spot in the following centuries.

Around the 15th century, the Aztecs found the city in ruins, with only large mounds, and called it “Teotihuacan,” meaning “the place of the gods,” in their Nahuatl language. They believed this to be the sacred place, according to the post-Classic myth of creation, where the gods sacrificed themselves to create the present world, the Sun, the Moon and lives of the natural world. This mythological concept of sacred space remained for centuries, and after so long, it was still applied to interpret findings of this ancient city in early 20th-century archaeological projects.

Recent excavations at the monuments are changing views on Teotihuacan’s mythological origin and providing new historical perspectives.

We now know that the pyramids did not sustain a single, permanent form for centuries, as Teotihuacan leaders modified, enlarged or partially destroyed the pyramids throughout the city’s history. Rulers used to perform sacrificial rituals of people and powerful animals at the monuments to proclaim their power with militarism, which had a great impact on urban life, as well as on other aspects of the Mexican Highlands.

Additionally, burial discoveries indicate that the three pyramids were closely related.

In summary, new data indicate that the people of Teotihuacan were obsessed with capturing their cosmological ideas at a large scale through human sacrificial rituals and sacred warfare.

Teotihuacan was one of the most influential pilgrimage centers of the North American continent, attracting numerous people from different ethnic groups under strong centralized government leadership.