ASU anthropology graduate student doing explosive and innovative research

Jayde Hirniak is a graduate student at the School of Human Evolution and Social Change and Institute of Human Origins.

Cryptotephra, or microscopic volcanic glass, are helping scientists learn more about human evolution and migration across the world.

One of the scientists working on this research is Jayde Hirniak, a graduate student at the School of Human Evolution and Social Change and Institute of Human Origins. During her time as a grad student Hirniak has worked with experts in the fields of archaeology, geology and volcanology across the world.

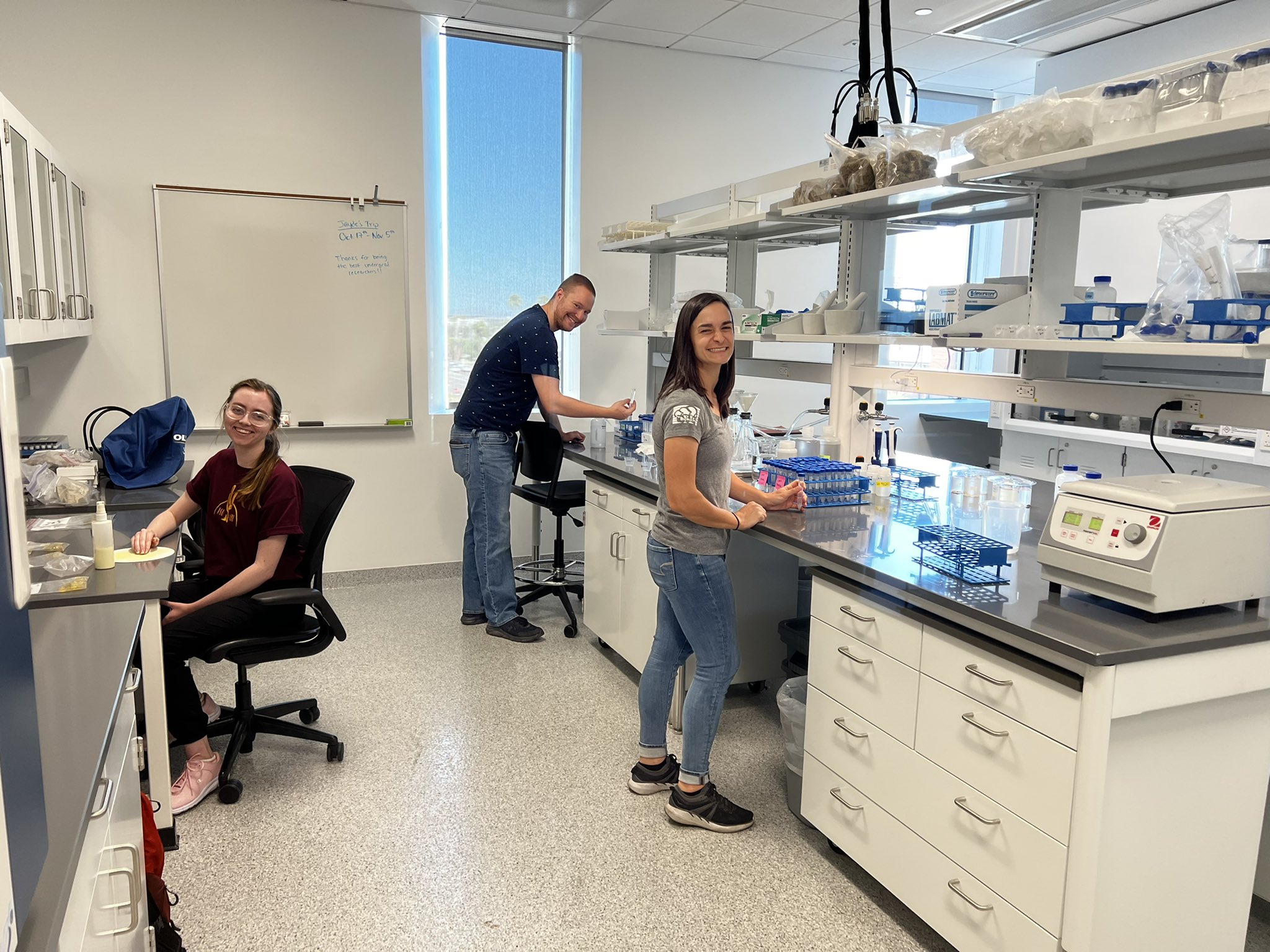

She is now working on her dissertation and was recently published in the science journal “Nature” for her cryptotephra work in new research about the Toba super-eruption. Hirniak also led the efforts to build a cryptotephra lab at ASU, which is now one of the few in the country.

“Every eruption has a unique signature, or fingerprint, that can be identified geochemically,” said Hirniak. “Therefore, when you identify these types of deposits (e.g., visible ash or cryptotephra) you can directly link them to an eruption and identify them on the landscape using this fingerprint.”

ASU News spoke with Hirniak, about her research, dissertation, mentors and time at Arizona State University.

Question: Regarding the paper in Nature, how does it feel to be published in the journal Nature as a graduate student?

Answer: It is a bit surreal. I have been working on the data for years and to see it finally published is a great feeling. I also never imagined to be published in Nature this early in my career.

I started working on the geochemical data back in 2021. I was working in collaboration with Gene Smith and he shared the data with me because it looked a lot like what we were finding in South Africa. However, the trace element chemistry had an interesting signature that at first, we could not figure out what was causing it (we called it a depleted signature). We see this same type of chemical signature at various sites in South Africa and Smith and I were trying to determine whether it was a signature that a volcano produced or if it was from post-depositional processes (i.e., weathering, anthropogenic processes, etc.).

So, I began helping Smith source the volcanic glass to an eruption and test the different hypotheses regarding this depleted signature. After chatting with various other geochemists and conducting some experimental studies, we were able to determine that the glass was from an eruption called the Youngest Toba Tuff and that this “depleted” signature was produced from the eruption. I am currently working on a manuscript that describes what caused this signature and I hope to publish it this year. This work with Smith not only helped get our Nature paper published, but it is helping me understand the results I am getting from my dissertation work throughout South Africa.

Q: To a non academic reading this - what do you research and why?

A: I use volcanic deposits, or tephra, to more accurately date and correlate archaeological or geological deposits. I specifically look at volcanic glass that is present within these deposits or sometimes isolated in the sediment.

During an eruption, the tephra is distributed along the landscape with larger fragments closer to the vent and smaller fragments further away from the vent. The far-traveled material (> 1000 km) is in the form of cryptotephra, or nonvisible volcanic glass, and during an eruption it can be deposited on the landscape within two weeks of the eruption (the amount of time it typically takes to settle out of the atmosphere).

Tephra can be directly dated to the time of the eruption or it can be geochemically traced to an already dated eruption. These deposits can also be traced along the landscape and used as distinct marker horizons. Every eruption has a unique signature, or fingerprint, that can be identified geochemically. Therefore, when you identify these types of deposits (e.g., visible ash or cryptotephra) you can directly link them to an eruption and identify them on the landscape using this fingerprint. This overall dating and correlation technique is referred to as tephrochronology and it is very important for dating archaeological or geological records.

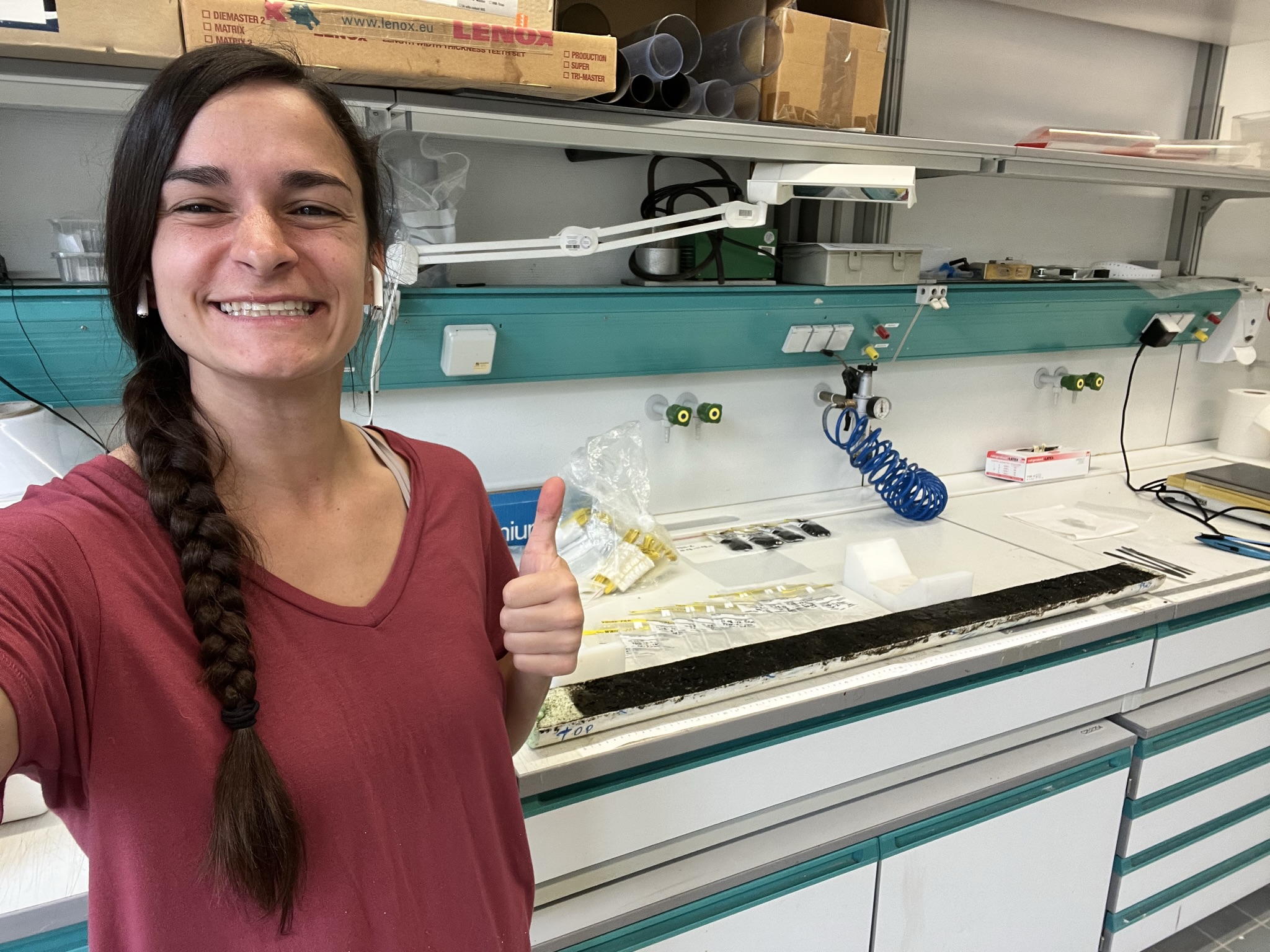

For my dissertation, I am examining multiple localities throughout South Africa that preserve cryptotephra from a supereruption called the Youngest Toba Tuff which erupted about 74,000 years ago. I am using this eruption and other identified eruptions to help refine the age models at various archaeological sites which is really important for understanding the timing of specific cultural events in the record.

Q: Why do you enjoy studying volcanic eruptions and what led you to this area of study?

A: I actually have been working in a tephra lab since I was an undergraduate at Rutgers University. I started as a student worker in Professor Craig Feibel’s lab in 2014. At first, it was a way to get lab experience, however, once I went into the field with Feibel, that is when I became hooked and my passion for geology began.

In 2015, I attended the Turkana Basin Institute Origins Field School in Turkana, Kenya and Feibel was my geology instructor. I remember learning about all of the volcanic activity in the region and how the tephra was used to date some of these famous hominin discoveries (which is what I do now!). On the weekends during our free time, I would help my TA collect field samples and she would teach me about the geology in the region.

I just remember being so fascinated by the fact that we could look at the sediment and based on what type of deposits were preserved, we could reconstruct what the landscape once looked like. In this area in particular, depending on what time period you were studying, the landscape looked very different than it did today and that story was hidden in the sediment that as a geologist, I was learning to read.

After the field school, I completed an honors thesis that focused on where famous hominins were preserved on the landscape and in what type of geological deposits. Throughout all of my work, I found that I was most interested in reconstructing the context of these famous finds. While there are multiple components to understanding the context, one of the most important, in my opinion, is determining how old the deposits are. This is what led me down the path I am currently on.

There are multiple ways to date archaeological or geological deposits. However, given the region I was interested in at the time, using volcanic deposits was one of the most opportune and reliable ways. Fast forward to graduate school and I began working with a volcanologist, the late Professor Emeritus Gene Smith with the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. While I was interested in studying volcanic eruptions in the past, I have to contribute my current passion for this to Smith. This was because he was also extremely passionate about studying volcanoes and what they could tell us about the past.

While we can use their deposits to date and correlate sites across the landscape, we can also use them to tell us about our futures. In fact, some of the most interesting work revolves around studying past volcanic eruptions to understand what might happen if one that size erupts today. There is also research that studies and monitors active volcanoes to better predict when it might erupt. While this is outside of the realm of what I study, Smith played a huge part in demonstrating to me how we can learn from these massive landforms that we coexist with today.

Q: Where have you conducted fieldwork over your career and what are your most memorable places you have visited?

A: I have conducted fieldwork in Italy, South Africa, Greece, Kenya and Western USA. I attended the field school at Turkana Basin Institute in Kenya in 2015 and then the International Field School on Site Formation in Athens, Greece in 2019. Between then, I have participated in geological field work with Gene Smith and Research Associate Racheal Johnsen studying the Twin Peak volcanic complex.

This is where I learned a lot about volcanology and how to study these deposits on the landscape. I also took the advanced field geology course at ASU with Amanda Clarke, professor at the School of Earth and Space Exploration, and had the opportunity to study deposits from Valles Caldera in New Mexico.

I also worked on two archaeological sites, Arma Veirana and Riparo Bombrini, in Italy for my master’s research and I attended multiple field seasons on those projects. Lastly, I have been working in South Africa since 2016 and I have excavated or worked as a specialist at six different archaeological sites throughout the Western Cape, Kwazulu-Natal, and on the edge of the Kalahari Basin. More recently, I conducted fieldwork through Washington and northern California investigating the impact of wildfires on historical archaeological sites. While that work was very different from what I typically study, I wanted to get more experience working on North American archaeological sites.

It is really hard to pick the most memorable places I have visited because each one is memorable in a different way. The field seasons in Italy were memorable because of the long hikes to the site and the incredible food that we had. We ate at a family-owned restaurant in town and the food was some of the best I have ever had (I still miss it!).

All of the field seasons I have spent in South Africa are also extremely memorable. From working on rock shelter sites perched high on a cliff overlooking the Indian Ocean to cave sites that involve a treacherous hike to access, each has had a unique and exciting experience tied to it. However, as I reflect, I think the most memorable field experience has been at Turkana Basin Institute during one of my first field seasons. This is where my passion for studying human evolution began and it kickstarted the path I am currently taking. I created lifelong friendships there and a curiosity for learning that I still hold today.

Q: Anything else you would like to add?

A: I would just like to stress how much of an impact Gene Smith was on all of my work and how I would not be where I am today without his help. Smith recently passed away and there is not a day that goes by where I don’t want to discuss volcanology with him. He was an amazing colleague, mentor and dear friend and I miss him immensely.